On September 5, 1892, some 15,000 people gathered for the 34th annual games of the Philadelphia’s Caledonian Club. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted on September 6, “there were several incipient fights, and quite a number of arrests,” before adding, “considering the size of the crowd, good order was preserved by the large force of patrolmen.” The article mentioned that one of the features of the event was a match between Philadelphia Athletic and Tacony. Athletic won, 3-1.

The large crowd at the Caledonian games, while not on hand for Athletic-Tacony game alone, surely must have gladdened the hearts of the city’s soccer community as the start of the Pennsylvania Association Football Union’s 1892-1893 season approached. With the Trenton Swifts joining the seven clubs that had finished in the 1891-1892 season, the league would field it largest roster of clubs since its founding in 1889. The prospects of both the league and soccer in Philadelphia were looking good. The Inquirer saw Philadelphia as a center for the game in the United States, writing on December 13, 1892, “Association football thrives in this city, but is known in few other places on this side of the Atlantic.”

It was an easy conclusion to reach; only three days before, twelve hundred spectators gathered to watch a match that ended in a draw between the first place Athletics and third place Tacony at the Philadelphia Base Ball Park, located at Broad Street and Huntington Streets. Although the attendance figure was paltry when one considers the park had a capacity of 12,500, that the park owners had recognized that money could be made during baseball’s offseason by hosting soccer games was the start of baseball-soccer connection in Philadelphia that would continue for decades.

Nevertheless, while baseball park owners were looking to capitalize on the thriving soccer scene that was reported by the Inquirer, the newspaper’s coverage of soccer, only a short time before regular with match reports after the PAFU’s Saturday matchday, was in sharp decline: before the December 13 article, save for two brief mention of games in the December 11 edition of the paper, the last Inquirer match report appears to have been on a preseason game in August. And this with the December 13 report noting that Athletic and Oxford topped the PAFU table with ten wins each.

Troubled times for league soccer

North End eventually dropped out of the league in March, 1893, and things quickly went downhill from there. By December, 1893 the PAFU schedule featured only three clubs, Athletic, Frankford and Tacony. Whereas in recent years Christmas Day had been the occasion for several soccer matches, only one was scheduled for Christmas of 1893, a non-league match “between two teams in the lower end of Germantown, known as the Wakefield and Smearsburg kickers.” What had happened?

While the Inquirer had reported in November 6, 1893 that “intercollegiate football [e.g. college football] is now all the rage” it also noted the “missionary spirit” of “the followers of association rules.” League soccer in Philadelphia wasn’t faltering through lack of interest or effort. What had happened was the Panic of 1893, an economic crisis that may have been worse than the Great Depression. Beginning with the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad in February of 1893, the stock market crashed, banks collapsed, factory work slowed or ground to a halt, and unemployment soared. The economy would not recover for four years.

Particularly hard hit were Philadelphia working class neighborhoods like Kensington, precisely those industrial neighborhoods that provided the strongest support for soccer. While Athletic won the Childs Cup for the 1893-1894 season, organized league soccer in Philadelphia was barely alive. Non-league clubs Haddington, Stenton, Jefferson, Manayunk, Excelsior, Eddystone, Mt. Vernon, Roxborough, Wissahickon, Brill (perhaps Philadelphia’s first factory-based team), and Celtic all played matches throughout 1894, sometimes against league clubs, more often among themselves. Not that non-league matches lacked in excitement. The Inquirer reported of a match on February 3, 1894 between Excelsior and Stenton, “The rivalry between the adherents of the two elevens became so intense that several pitched battles occurred, and the police were compelled to interfere.” Five hundred spectators were on hand for the game, won by Excelsior, 4–3.

Intercity matches sustain the game and lead to a new opportunity

What sustained soccer in Philadelphia at this time was the continued organization of intercity matches, particularly against teams from New York and Trenton, although greater distances could be involved. Frankford had traveled to Pittsburgh to play a game on October 22, 1892, losing by a 4-0 scoreline that was probably influenced by the fact that Frankford’s goalkeeper was injured early in the game and played most of the first half as a field player before returning to goal in the second half. On February 22, 1894 at Forepaugh Park — former home of the American Association Philadelphia Athletics and the Players League Philadelphia Quakers baseball teams and located at Broad and Dauphin Streets — some fifteen hundred spectators gathered to watch what was supposed to be the deciding game for the “Intercity Championship” between the All-Philadelphia team and the Cosmopolitans of New York. Played on “a field covered with snow and in a raw biting wind,” the game ended in a 3–3 draw.

The crowd included “not a few ladies” dressed in the red and white colors of the home team, as well as a delegation of University of Pennsylvania football players. The Inquirer reported on February 23,

The Varsity boys thought the sport rather tame at first, but after Captain Walker of the New Yorks, was accidentally kicked in the stomach and laid out for a few minutes [University of Pennsylvania football player] ‘Bucky’ Vail became enthusiastic and said he believed the game might come into popular favor, after all.

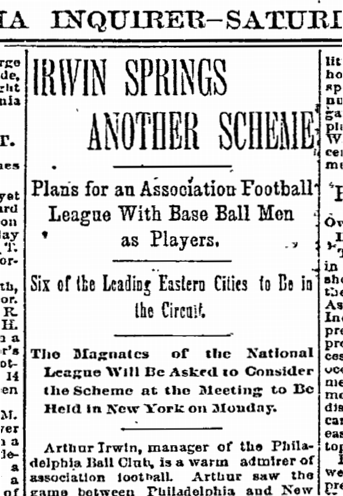

Perhaps most importantly, Arthur Irwin, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies, also was at the game. Two days after the draw, the Inquirer reported that Irwin, “a warm admirer of association football,” had announced a “scheme” to have “a league of association football clubs composed of professional base ball men, and to have Brooklyn, New York, Washington, Baltimore, Boston and Philadelphia as the six cities in the circuit.” The league would play its games in the winter to “enable the ball players to keep in good condition for their season’s work.” Irwin planned to bring up his “scheme” at an upcoming meeting of “baseball magnates” in New York.

The New York-Philadelphia series, the first game of which had been played two years before, was finally decided on Easter Saturday, March 24, 1894 when the All-Philadelphia team defeated the Cosmopolitans at Forepaugh Park, 4–0. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on “Fully 2000 persons, including many women” were at the game, as were Irwin, the English-born Harry Wright, former manager of the Philadelphia Phillies and future Hall of Famer, as well as two Phillies players, Charlie Reilly and future Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty. Two days later at Forepaugh Park, an All-Philadelphia team that included five players who had defeated the Cosmopolitans lost to an All-New Jersey team 2–1 “composed of players from Warren, Newark, Kearney and Trenton, N.J.” The Inquirer reported that, despite being a very cold day, “a good-sized crowd was present, including a number of women.”

The birth of professional league soccer in Philadelphia

Arthur Irwin’s “scheme” for a professional football league came to fruition on June 19, 1894 with the announcement of the formation of the American League of Professional Football Clubs. Irwin was announced the temporary president of the league, which was “backed by the magnates of the six leading Eastern clubs of the National Base Ball League.” The Inquirer reported on June 20,

The object of the league is to play football games in each of the represented cities from October 1 until January 1. Each city will be represented by the strongest players that can be secured. Home talent will be given the preference. The American Association Football rules of ’94 will govern all contests…The Philadelphia Club has already engaged seven players.

The announcement also stated, “The Sunderland Football Club, of England, will probably come here in the fall for a series of games with the clubs of the league.”

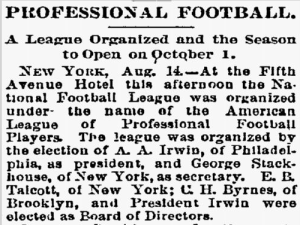

A meeting in New York on August 14 formalized the formation of the league under the name of the American League of Professional Football Players (ALPF). The Inquirer reported the next day the league had adopted a constitution “built on the same lines as that of the National Base Ball League, but not…so bulky,” with Irwin the elected president. The season would now run from October 1, 1894 to July 1, 1895. The announcement repeated the earlier report that the Sunderland Football Club of England “will visit this country” to play a series of exhibition games with the league.

Further details were reported by the Idaho Daily Statesman on August 18: “Contracts will begin to run Sept. 15 and extend through three months. The Championship season will begin Oct. 1 and consist of 20 games for each club, 10 at home and 10 abroad. The six clubs have signed a partnership agreement extending over three years, and each member is further bound by a guarantee fund.”

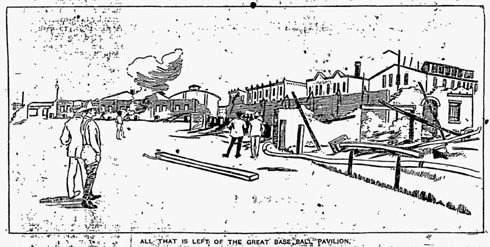

While Irwin had said in February that the purpose of the league was to keep baseball players “in good condition,” it seems apparent that the main purpose was to make money by staging soccer games in otherwise empty stadiums during baseball’s long off-season. By the time of the announcement, Irwin had a further incentive to make some extra money: on August 6, the Philadelphia Base Ball Park, home ground of the Irwin’s Philadelphia Phillies, was almost entirely destroyed by a fire. Only the exterior outfield wall remained intact and for the rest of the season spectators were seated in temporary stands.

Whatever the motivations for the creation of the league, Steve Holroyd describes in “The American League of Professional Football, 1894” (Soccer History, 2006) that the ALPF owners “were anxious to impose the same monopolistic conditions” they enjoyed in baseball. With the retention of the “reserve clause” in ALPF player contracts—which would remain in effect in baseball until the advent of free agency in 1976— players were potentially “little more than chattel to the owners.” David Goldblatt notes in The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (2006), “the commitment and seriousness of the baseball franchises was questionable”: games were largely scheduled on weekdays rather than on the weekend, when most of the potential working class audience would have been able to attend.

Doubts about soccer’s potential as a profitable draw were also revealed by the use of baseball team managers to coach most of the soccer franchises, and newspaper reports suggesting that popular baseball players would play on the soccer teams. Interestingly, while baseball owners in the US were dabbling in soccer, a handful of professional soccer clubs in England were attempting to introduce baseball there through the creation of the National Baseball League of Great Britain and Ireland, founded in 1890. An article in Harper’s Weekly on April 21, 1894 explained the reasoning behind the creation of the league was “to enable club-managers to come out nearer even, pecuniarily speaking, by keeping their players remunerative in summer, after the football season is over and ‘gates’ are of the past.” Which is to say for the very reason that baseball teams were trying to introduce soccer: to make money in the offseason.

Illustration from the front page of the August 7, 1894 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer showing the aftermath of the Philadelphia Base Ball Park fire.

Rival professional league and teams

The ALPF was greeted with suspicion in soccer circles. Holroyd notes the American Football Association, organizers of the American Cup tournament, viewed the baseball owners as “carpetbaggers.” That suspicion soon became manifest in action. On September 16, the Boston Daily Journal reported a new rule had been adopted at the AFA’s annual meeting in Newark the day before banning any player who “signed a contract and played” with a ALPF team from participating in a AFA sanctioned game. “This course was found necessary because of the action of the base ball magnates, who, it is asserted, are trying to induce association players to join the league.”

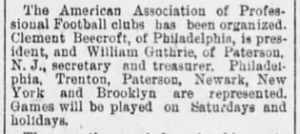

On September 1, 1894, the Scranton Tribune reported the formation of a rival professional league to the ALPF, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF) with Clement Beecroft, the inaugural president of the PAFU, named as president of the new league and William Guthrie of Paterson, New Jersey, as secretary and treasurer (curiously, as of this writing, I can find no reports on the formation of the league in Philadelphia newspapers). In other words, with Irwin and the ALPF, and Beecroft and the AAPF, Philadelphia sports figures had a hand in the founding of the first two professional soccer leagues in the US.

The Tribune report said the AAPF would include teams from Philadelphia, Trenton, Paterson, Newark, New York, and Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on September 3 “the circuit that the professional league has arranged includes all the association foot ball centers in America, barring Boston, Fall River, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Chicago.” Games would be played on Saturdays and holidays, with Forepaugh Park reportedly being the home grounds of the Philadelphia team.

Beecroft’s Philadelphia AAPF team would beat Irwin’s ALPF team for the honor of playing the first professional soccer game in the city, the Inquirer reporting it played the “first professional game of association football…in this city” on Saturday, September 29, 1894 at the Tioga Athletic Grounds, against the Trenton AAPF team in front of about a thousand spectators. The Philadelphia Times reported on September 30, “It was evident immediately after the opening of the game that the Trenton team was outclassed. It was only a question of how many goals the home club could place to its credit.” Philadelphia scored five goals in the first half, and six in the second half, to finish with an 11-1 victory. Fielding players who had previously appeared on All-Philadelphia teams in intercity matches, the team would be referred to in newspaper accounts as “the American Association” Philadelphia team, or as the “Philadelphia Association.” Among those on the roster were six players who had been on the Tacony PAFU team the previous season.

Contemporary accounts generally did not refer to Irwin’s professional team as the Phillies. Rather, it was referred to as “the Philadelphia Football Club, of the National Association” or “the Philadelphia National Association Foot Ball team” in newspaper reports because the league it played in was backed by baseball’s National League. The Philadelphia ALPF team played its first game two days after the Philadelphia Association team on October 1, defeating a picked eleven 3-0 at the Philadelphia Base Ball Park at Broad and Huntington Streets, although the Inquirer’s brief report on the game does not say who exactly selected the players on the picked team. The next day, the Irwin’s team defeated Philadelphia Wanderers, 3–1. Neither of the Inquirer reports on the games give an attendance number. Given that the team’s first two games were played on a Monday and a Tuesday, we can assume attendance was small: the majority of soccer’s fan base in Philadelphia was probably at work, if they were fortunate enough to have a job. If they were out of work because of the ongoing economic crisis, committed fans may have chosen not to spend what little money they had on attending an upstart professional team.

The ALPF season opened on Saturday, October 6 with Irwin’s team losing 5–0 on the road to New York, and Boston defeating the visiting Brooklyn team, 3-2. Irwin’s team hosted New York on Tuesday, October 9, this time losing 5–2. On Thursday, October 11, Irwin’s team lost 2–1 on the road to the Washington Senators backed ALPF team at National Park. Still in the Capital, Philadelphia secured its first win in league play the next day, defeating Washington, 3–2, in front of a crowd of 600 spectators.

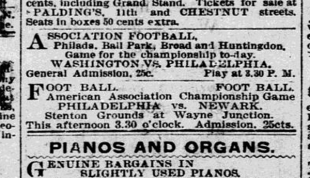

On Saturday, October 13, the Philadelphia ALPF team was scheduled to host the Washington team at Philadelphia Base Ball Park, the same day and time Beecroft’s AAPF Philadelphia team was scheduled to play the Newark team at Stenton in Wayne Junction. In the event, the Philadelphia Times newspaper reported the Philadelphia-Washington game was postponed until Monday, October 15 because of bad weather. The postponement was perhaps fortuitous for the Irwin’s side — even though they would have played at home, it would have been the team’s third game in three days.

The Philadelphia-Newark game was played, although the game happened under controversial circumstances. The teams had faced one each other in Newark on October 6 with the Philadelphia team returning home the 2-1 winners. On October 11, the Philadelphia Times, with typical hometown hyperbole, described the Philadelphia team as being “considered the finest in this country.” The preview continued,

The Newark boys are determined on this occasion to wipe out their defeat of last Saturday, and on the other hand Manager Beecroft’s team are confident they will continue their unbroken record. Altogether this game will be one of the best exhibitions of Association foot-ball ever seen in this country. Preparations are being made for a large crowd.

General admission entry to the game cost 25 cents with grand stand seats available at 50 cents. But, with more than a half an inch of rain falling on the city that day, attendance was poor, despite the interest in the game, and the Times reported on October 14, “When Mr. Beecroft got out to Tioga yesterday, he at once saw the gate would amount to nothing, so he decided the game off.” However, having made the effort to travel to Philadelphia, the Newark team refused to accept the cancellation and lined up on the field. The Times reported, “After scoring a goal the referee awarded them the game.”

Now it was the Philadelphia players turn to make a stand. The Times report continued,

The Philadelphia players then made a demand for their overdue salaries, and that not forthcoming, they gave their manager quite a talk and decided to play the game anyhow. This they did, and won after a desperate fight by the score of 2 goals to 0. The men say they will not play with Beecroft’s team any more, and as they are fighting mad it looks as if he would have some trouble to keep them in line.

Two days after its match report, the Times published a retraction. “Through being misinformed,” it had reported the players had not been paid: “This, it appears, is not true, for the salaries had been paid on the day previous.” The retraction noted that a letter to the paper’s sports editor from “President Fogel, of the Philadelphia Club…shows that the men had been paid right up to date, and that, too, in strict accordance with their contracts.” Philadelphia faced the Paterson AAPF team away on October 20 in a game that ended in a 4-4 draw.

Philadelphia’s rival professional teams were scheduled to play at the same time on October 13, 1894 but poor weather saw the Phillies game postponed. From the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Despite the poor results and attendance, the Inquirer remained optimistic about the prospects of the Irwin’s soccer team and the ALPF. The Inquirer noted on October 14, though soccer had been played in Philadelphia for years, it had “been patronized mostly by men who played on the other side of the Atlantic”; with the formation of the ALPF “it looks as if the game would soon become popular with the masses.”

There is sufficient rough play to add zest to the sport and the kicking and the “head play” combined with sprinting are features which cannot help but interest. Most of the players are Englishmen and Irishmen and some have been imported. As soon as they become better known to the public much more interest will be added to the game.

The Inquirer does not name who the “imported” players were, if the reference is to players on the Philadelphia ALPF team. The Philadelphia Times reported on October 9, “Davy Wilson, the best Association football player in town,” had signed with the team and would be its captain. The report continued, “He has a brother now playing on the famous Sunderlands, and when in England played on that team himself. ” The New York Herald-Tribune on October 10 referred to Wilson as “Philadelphia’s champion fullback…late of the Sunderland club, of England, the English champions.” After that, outside of goalkeeper Deardon and halfback/forward Brennan, both of whom had been on the Frankford team and had appearances on All-Philadelphia sides for earlier intercity matches, the origins of most of the Philadelphia ALPF players are murky.

Details are clearer about the Philadelphia connections of players on other ALPF teams. In a October 1 report at the Boston Globe, Washington Senators owner Earl Wagner said of his soccer team’s roster, “Most of these have played professionally in Philadelphia and Trenton, where the game is popular, but are graduates of the game in England.” Among those mentioned is Tom Riley, a forward who, before playing for Philadelphia’s Frankford team, ended “his English career as a member of the champion Corinthians.”

The collapse of the ALPF

Irwin’s Philadelphia ALPF team won their second league match on Monday, October 15, defeating Washington 4–1 in the postponed game at home at Philadelphia Base Ball Park. Among the players on the field that day for Philadelphia were at least two members of the Phillies baseball team, Charlie Reilly and future Hall of Famer Sam Thompson. Known as “Princeton Charlie” after his place of birth, perhaps Reilly had watched or played soccer-style football while growing up in Princeton, that early center of collegiate soccer? If so, that might explain why he was, as the Inquirer reported on October 16, “ejected from the field for wrestling.” The game was also notable for the apparent use of substitutions, a practice that would not become generally allowed in soccer for decades to come. In the event, Reilly played as a midfielder and is the only Phillies baseball player to have played in most of the Philadelphia ALPF games.

One day later on Tuesday, October 16, the Philadelphia, without Reilly in the lineup, were crushed on the road 8-1 at Eastern Park by Brooklyn, a side stocked with players from the Fall River club in Massachusetts. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on October 17 that Irwin’s team was “toyed with by the local cracks…Before twenty minutes had passed on the field it became manifest that the Quakers were not in the hunt.” The rout was so comprehensive the Daily Eagle reported that after the home team scored the eighth goal, “the Quakers went to pieces and had there been more time the Brooklyns might have rolled up a score which would have looked like a bowling game.”On Thursday, October 18, the Philadelphia again lost to Brooklyn, this time 3-1.

On Saturday, October 20, the Philadelphia lost 5–2 at home to Boston, a team filled with players from soccer hotbeds Fall River and Pawtucket, in front of four hundred spectators at Philadelphia Base Ball Park. Not only was it a poor showing on the field, it was a poor showing for a Saturday match, particularly when one considers that the Inquirer had reported a match in Baltimore between the Orioles-backed ALPF team and Washington drew four thousand spectators only two days before (Baltimore and Washington papers put attendance for the game at between 2,500 and 3,000 spectators). It was the last ALPF game the Phillies played. The same day, the league announced it had suspended operations. After all of the hope and hype for the prospects of America’s first professional soccer league, the ALPF had collapsed just 14 days into its first — and only — season.

While a Philadelphia Times report on October 21 cited the “late period at which the association was able to get underway… and the difficulty of avoiding conflict with the regular college foot-ball games” as the reasons for the cessation of the league, poor planning, bad scheduling of games, a growing scandal about the use of imported players in Baltimore, and rumors about the formation of a rival professional baseball league were all contributing causes. Sporting Life reported on October 27, “A prominent member of the Association says the failure to make a success of of the enterprise was largely due to the fact that the members had failed to take the advice of persons who could have aided them, and since the opening of the season over $2000 had been lost.” ($2,000 would be around $54,000 today.) Whatever the case, an Inquirer report on October 27 was blunt: “Association football doesn’t attract the crowds that it was expected to and the result is that the American League of Professional Football Clubs, which manager Arthur Irwin organized, has gone to the wall.”

With the exception of some very large crowds in Baltimore, attendance had been dismal throughout the league. A game between between Boston and New York on October 18 drew 50 people. The largest home crowd for a Philadelphia ALPF game was reported in the Inquirer‘s October 27 article on the league’s demise as “525” for the Philadelphia-Boston game, although the Inquirer match report for that game puts the attendance at “about four hundred.” Irwin’s team wasn’t making money on the road either: the Inquirer report on October 27 said the team had received a mere $9.22 for two games in Brooklyn and $60 for two games in Washington, ridiculously low figures when one considers that the entrance fee for matches was 25 cents, half of what it cost to see a professional baseball game.

A Brooklyn Daily Eagle report on October 21 quoted ALPF Secretary George E. Stockhouse as saying the league would “reorganize on somewhat different lines” for the 1895 season. As Grant Czubinski makes clear in his series on the ALPF, the Baltimore Orioles and Washington teams were particularly keen to continue, with the Orioles “ready to defend the inscription on their first soccer pennant ‘Baltimore Champion Football Club of the United States, 1894.'”

Despite the poor record of the Philadelphia ALPF team in league play, the dismal attendance figures, and the general evidence that he would do best to stick with baseball and leave soccer to those with some experience in the game, the Inquirer reported on October 27 that Irwin planned to “organize a strong team of local players to play at Philadelphia Ball Park on Saturdays.” At least he now seemed aware of the potential for soccer’s working class fan base to come to see a soccer game if it was scheduled at a time when they could attend. (Philadelphia’s record in ALPF play has been variously reported in later histories. Sam Foulds and Paul Harris reproduce in America’s Soccer Heritage (1979) the 3-5 record reported by the Baltimore Sun on October 22, 1894. In an article at the American Soccer History Archives, Holroyd has their record as 2-7, as do Roger Allaway, Colin Jose, and David Litterer in The Encyclopedia of American Soccer History (2001). As of this writing I have been able to find eight match reports for Philadelphia ALPF games resulting in a 2-6 record, the team being outscored 14-31. I believe the discrepancies — an additional win with the Sun and America’s Soccer Heritage, an additional loss with Holroyd and The Encyclopedia of American Soccer History — may come from the inclusion of a non-league result.)

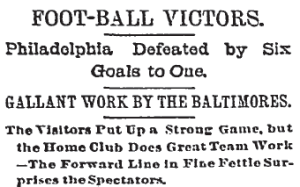

In the meanwhile, the Baltimore Sun reported on October 22 that Irwin had “challenged the Baltimores to play” what turned out to be a series of three games, all in in Baltimore. Perhaps Irwin was hoping to make at least some money by playing in the city that had had the largest attendance in the brief existence of the league? After all, the Times reported when the ALPF folded, “It was determined that all clubs should pay salaries in full up to November 1, 1894.” If that was the case, Irwin would be disappointed.

The teams met at Union Park on October 23, the Sun reporting, “Threatening weather kept many spectators away.” After the first half, Baltimore led 3-1. By the end of the game, the scoreline was 6-1. On October 25, the teams played again. For Philadelphia, Charlie Reilly, who had not played in the previous game, returned to the lineup — to play in goal. The Sun reported Reilly “had plenty to do, and he did it so successfully that the spectators applauded him.” Despite the applause, Irwin’s side was once again, as the Sun reported, “clearly outclassed,” losing this time, 4-0. The teams met for the final game of the series on October 27. Philadelphia managed to score four goals, but still lost, 6-4.

The Baltimore team continued for a few weeks more, traveling to Fall River, Massachusetts to play the remnants of the Brooklyn ALPF side in what was supposed to be a six-game series to decide the champion of the US. Going with them was Phillies inside left D. Cochran, who signed with the Baltimore club after the series against Philadelphia. In the first game, the teams drew 2-2, with the Brooklyn/Fall River team winning the next two games. The rest of the series was never played — a horse show at Union Park while the team was in Fall River had rendered the pitch unplayable — and the Baltimore side officially disbanded on November 20, 1894.

The first professional soccer league in US history was finished. Given its poor showing, the league’s untimely end was perhaps in some ways merciful for the Phillies-backed team.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia’s other professional team continued to play. In just a few years, it would win Philadelphia’s first national title since the Athletics won baseball’s American Association championship in 1883.

The series continues next week. Special thanks to Grant Czubinski for sharing with me copies of articles from the Baltimore Sun and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on the Phillies soccer team.

I see you don’t monetize your blog, don’t waste your traffic,

you can earn additional cash every month because you’ve got high quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra bucks, search for: Boorfe’s tips

best adsense alternative